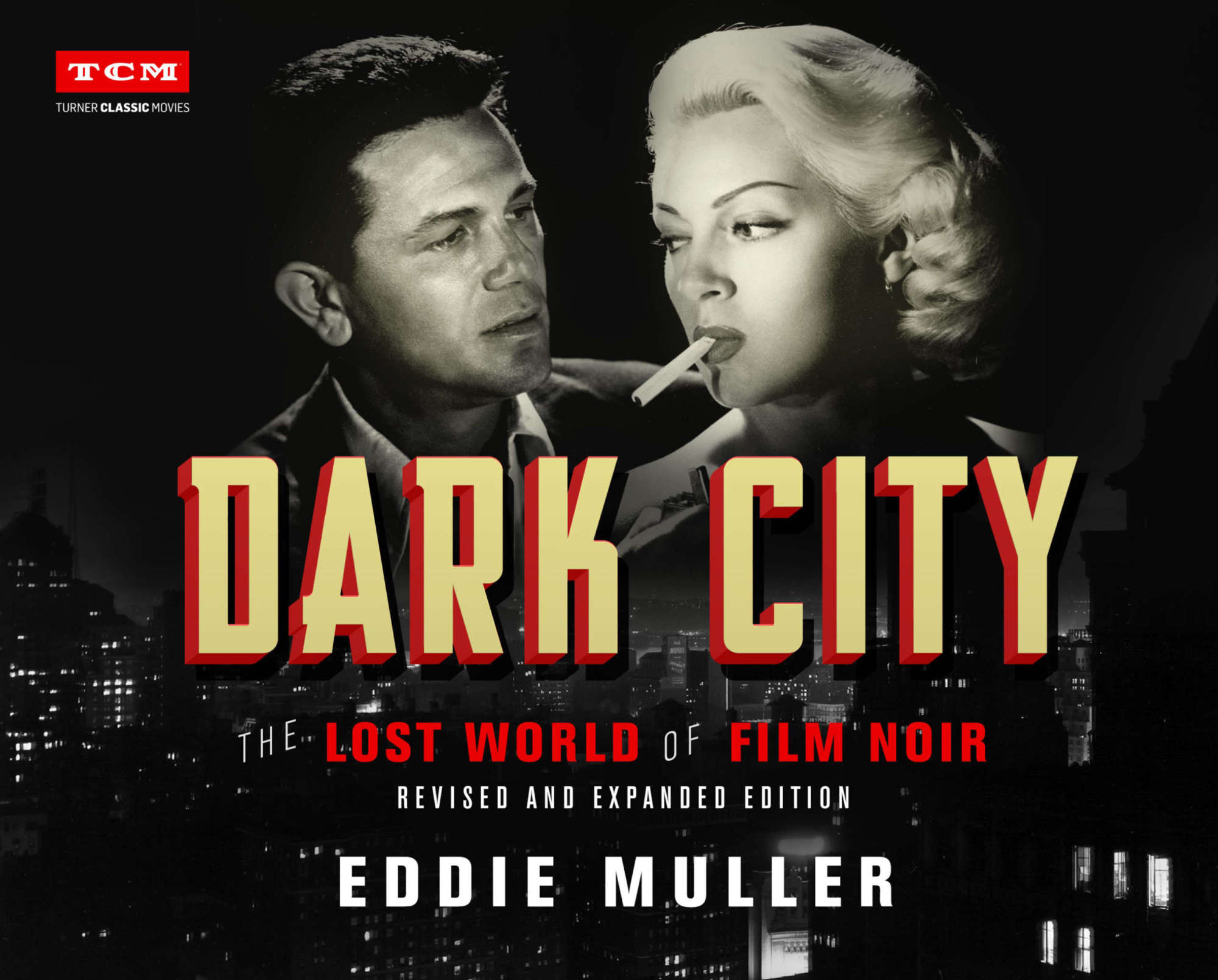

Released last month, the revised and expanded edition of Eddie Muller’s Dark City is “a film noir lover’s bible, taking readers on a tour of the urban landscape of the grim and gritty genre in a definitive, highly illustrated volume.”

Dark City has been expanded with three new chapters and restored photos throughout that “illustrate the mythic landscape of the imagination.” It’s a place where the men and women who created film noir often find themselves dangling from the same sinister heights as the silver-screen avatars to whom they gave life.

Originally published in 1998 and written by Eddie Muller, host of Turner Classic Movies’ Noir Alley, the book “explores Hollywood in the post-World War II years, where art, politics, scandal, style–and brilliant craftsmanship–produced a new approach to moviemaking, and a new type of cultural mythology.”

I spoke with Eddie Muller by phone to discuss the new edition and the book’s decades-long legacy.

Cinepunx: Reading the intro to Dark City, I find it really great that you discovered noir through seeing films on television and now you’re helping bring them to people yourself.

Cinepunx: Reading the intro to Dark City, I find it really great that you discovered noir through seeing films on television and now you’re helping bring them to people yourself.

Eddie Muller: Yeah, that is good, isn’t it? It’s funny. I hadn’t really made that connection because, because when I wrote that introduction, it was 1997 and I had no idea that, that I would end up being on TCM, which was pretty young itself at the time I wrote that introduction. It’s a fascinating trip so far.

No, but that is great. It’s a breasting observation that you make because I hadn’t really, I hadn’t really thought of that.

The book is now readily available to people again, but I know it’s changed some. What was the process of revisiting also revising Dark City?

I have to be very careful the way I phrase this: for a long time, it was very frustrating because the original book opened up so many opportunities for me. It made me a film programmer because the American Cinematheque in Hollywood invited me to, to program a festival based on the book and then that became an annual thing. In many ways, that’s what kind of put me on TCM’s radar.

There were several things that got me on TCM’s radar, but I know the festival in Hollywood that I did was one of them and in the course of programming those festivals, I uncovered so many more movies that I had not been able to write about. And then, I created the foundation and then we were saving these movies and so, I’m saying it was a bit frustrating because I wanted to do another edition of the book, but then every time I thought, “Now is the time,” then I’d be afraid: “Well, there’s more stuff that I could still discover and I can’t do an edition of this book every three years,” you know?

In the end, although it was very frustrating that I couldn’t get the rights to the book back from St. Martin’s Press for a long time, the fact that it happened when it did–which was just two years ago–was very fortuitous because it felt like now is absolutely the right time, because I’ve got the show on TCM, I’ve restored a lot of movies, and I’ve learned so much more about the subject that it embarrasses me, almost, to think that people were calling the original volume “definitive.”

It’s like, “Oh, it’s not,” because even this one, I already feel like there are three or four films I really would have loved to have talked about in this that aren’t in there right now.

Which discoveries that you’ve made in the intervening 20 years between its initial writing and the revised edition were you most excited to put in this new edition?

I would say probably Woman On The Run is probably the one, because that’s a film that is very close to me. It’s very rare when you have a personal relationship with a film where–I don’t want to sound like I’m tooting my own horn here or something, but the fact of the matter is like I was the person who rediscovered and restored that.

If I had not done that, that film would be unknown today so that definitely is very important to me. I feel that way about Too Late For Tears, as well, and Cry Danger and The Man Who Cheated Himself. All the films that we found and restored through the Film Noir Foundation were really important for me to be able to talk about in the context and being able to add them to the template that I created back in the late ’90s and say, “Here’s some that slipped through the cracks.” I think that alone gives people who read the book a very good idea about film restoration and preservation and how movies can actually disappear.

All of those films that I just mentioned are movies I brought to TCM. They all had their TCM premiere because of me. Because of the work of the Film Noir Foundation and all the people who donate to the foundation, that enabled us to restore these pictures and then get them on TCM so that now people actually see them.

As part of that original run of programming films and getting to do Noir Alley and with the foundation, you’ve gotten to meet some of these people who made the movies. How has that affected your perception of these films?

I think it gives me a well-balanced perspective. I focus on the practical as much as I focus on the theoretical, in writing about film and so, knowing the people, I have a real sense of making movies as well–what John Ford would call “a job of work.” This is what these people did for a living. It was a profession to them and a craft. For some, it was an art. For others, that was just a job, and I respect all of that.

That’s been really important for me to see it not with my head in the clouds about, “God, I love these movies and they mean so much”–and they do!–but coming at it from a very practical sense of “This is why this movie matters. Even though it’s too bad that this actor couldn’t sustain this kind of thing that they developed,” it’s this tremendous story to me.

I write about it more as a historian than a film critic or something. I see it as a storyteller. I’m not interested in writing graduate thesis or something about these movies. I’m just really fascinated by the fact that this is what people can do for a living and what that means to them. I can relate to that because I have a weird job. I’m on TV and I write about movies and stuff. That’s an odd way to make a living, really.

One of the things I really appreciate about this edition is the way it’s put together and the way it’s laid out is that it is a very good historical book and I want you to understand that I do quite enjoy the words in the book, but the pictures are just amazingly gorgeous. This is a beautiful looking book.

I greatly appreciate that, Nick, because that was the plan. The original edition of the book, it was my second book so, of course I was thrilled that it got published and it opened up every door for me, but I’d be lying if I didn’t say, “I’m not thrilled with this paper stock” and “the quality of the reproductions could have been a little better.” I’m not being critical of anybody when I say that, but it now looks like the book I wanted it to be 22 years ago. I’m really thrilled about that.

I couldn’t be more grateful to TCM, but to Running Press and my editor there. She fought to maintain the things that I thought were really important about it, like the odd dimensions. The fact that it’s a horizontal book, not a vertical book, was very important to me. There’s a lot to do with how it reads and how the photographs play as part of the narrative. I’m really thrilled about all of that.

I really did appreciate your comments about enjoying the words. Somebody once said to Lawrence Block, “When you’re writing a book, what’s more important: the characters or the plot,” and he said, “What side of the dollar bill has more value: the front of the back?” That’s exactly the way I look at the interplay between the words and the pictures in my book. You can’t separate them. They have equal value and that’s how it was designed.

The book does end at a very certain point. What are your feelings on neo noir and your Blade Runners, your Bricks, your Under the Silver Lakes, and what have you?

There’s more of it than people realize. That’s what’s so funny. The thing is that I consider all of this to be ongoing, right? The basic principles here and the basic tenets of neo noir is fine. Basically, what it is is that noir will follow the criminal more than it follows the people hunting the criminals. That’s sort of what it’s about: what happens that makes people capable of committing crimes that they never thought they would commit?

Obviously that story is not going to go away, but what makes the original film noir era so special is that it was so concentrated. You can see it: there was a look about noir that the gates opened and so, the writers and directors started making a bunch of these movies all at one time, so much so that it was obvious to to exhibitors: “What’s happening? This is weird. You’re making too many of these movies.”

The concentrated period in which that movement existed is what makes people connect to noir and say, “It started in 1941 and it ended in 1958” or something like that, but to me, noir has been around for so long now. It’s not a movement really, but it obviously is continued, but it doesn’t have that same cache of it at this point.

It’s been going on since the 1960s, and they’re still making these films, and now they’re all over TV. I think it’s really interesting to see how the times sort of dictate how people are going to approach crime stories. So right now, with noir, we’re seeing a lot of movies where there are female protagonists that you never saw before in these films.

The new Soderbergh film, No Sudden Move, where the character Don Cheadle plays in that movie would have been a guy off to the side of the frame in a movie in 1956. He would have barely registered, but now he’s the lead character in the movie. I think that that’s all very significant and I think that noir stories generally reflect what’s going on in the culture in the time they’re made, even if they’re a period film that’s set in the 1950s. It’s like, “Now we’re going to tell you a story that we never would have told you in the 1950s, because the culture has progressed.” I find it endlessly fascinating.

Eddie Muller’s revised second edition of Dark City is available now from TCM and Running Press.