In 1938, Orson Welles may or may not have caused a panic throughout the United States when he adapted H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds” as a radio play. Over the course of 60 minutes, Welles ‘interrupted’ the normal Mercury Theatre broadcast with news bulletins stating that Martians were invading Earth, but, by the end of the show, audiences across the country quickly came to the realization that there had been no attack. Buildings still stood where they had previously. The streets were empty except for some very confused crowds. And, sadly, there were no flying saucers hovering in the skies. When the American public then found out it had been an elaborate prank and that they had been taken for fools, some were outraged, but many more were amused. Or as the Chicago Tribune ever so politely put it, “perhaps it would be more tactful to say that some members of the radio audience are a trifle retarded mentally, and that many a program is prepared for their consumption.” Probably in part because of the wildly divergent, yet incredibly passionate reactions to the program, the legend of the radio play grew and it took on a life of its own. New pranksters would emerge to pick up where Welles left off.

Fast forward 54 years and take a long leap across the Atlantic to England: the BBC’s Screen One was looking to scare a different set of English-speaking audiences for Halloween, so on October 31, 1992, they dropped Ghostwatch on an unsuspecting British public.

Unlike War of the Worlds, Ghostwatch was treated as a feature-length production and ran for 90 minutes. Presented as a special investigation into the paranormal, Sir Michael Parkinson sat in Studio D and led audiences through a supposedly live talk show, while cutting with increasing urgency to actress and TV personality Sarah Greene, live from a haunted house in London. Parkinson, known for his work as an actual broadcaster and talk show host, interviewed a parapsychologist in the studio while Greene, known primarily for children’s show Going Live!, led a family through their haunted house looking for evidence of the supernatural. Both offered increasingly confused and shocked expressions as the program dragged on and spooky events started to plague both locations, culminating in one of the best shock endings in the history of television — Parkinson wandering through a pitch black set, reciting “Round and Round the Garden” to himself, while Greene is locked in a cupboard with the poltergeist and the whole of England descends into chaos.

The first indication that something was off about Ghostwatch should have been that it was being presented as a part of Screen One, an anthology series composed of one-off telefilms. In fact, it was the last episode of the program’s fourth series. Another indication should have been that the story of the haunted house in London was familiar. Writer Stephen Volk made no attempt to hide the fact that he had taken liberally from the Enfield Poltergeist, a story that had captured the imagination of the British tabloids of the late 1970s. But, more than any of that, it’s ending was relaying a scenario in which an entire nation was collapsing due to mass hauntings, and this was something that, by 1992, should be easily disproven with a quick phonecall.

Oddly, Ghostwatch incited much of the same outrage as War of the Worlds. Tabloids raged and prudes complained. What set Ghostwatch apart from War of the Worlds in the eyes of many observers was execution. The purpose of Welles’ Halloween prank was never unclear even if it was able to confuse a few people. It was a drama intended to capture the attention of radio audiences. It maintained its news bulletin format for most of the program but broke continuity just before the final third as a voice broke into the broadcast to announce that the program was a dramatization, after which point the story veered from faux-news into more of a traditional radio play and Welles delivered a monologue. Ghostwatch never broke continuity, up to and including its bleak ending. This made it too realistic for many and as a result it was blamed for inflicting psychological trauma on audiences to such an extent that it may have caused PTSD and even a suicide.

That doesn’t mean Ghostwatch would be the end of Halloween pranksters trying to put one over on an unsuspecting public with a faux-documentary. But after Ghostwatch had set the bar so high, it would be hard for another media prank to match that.

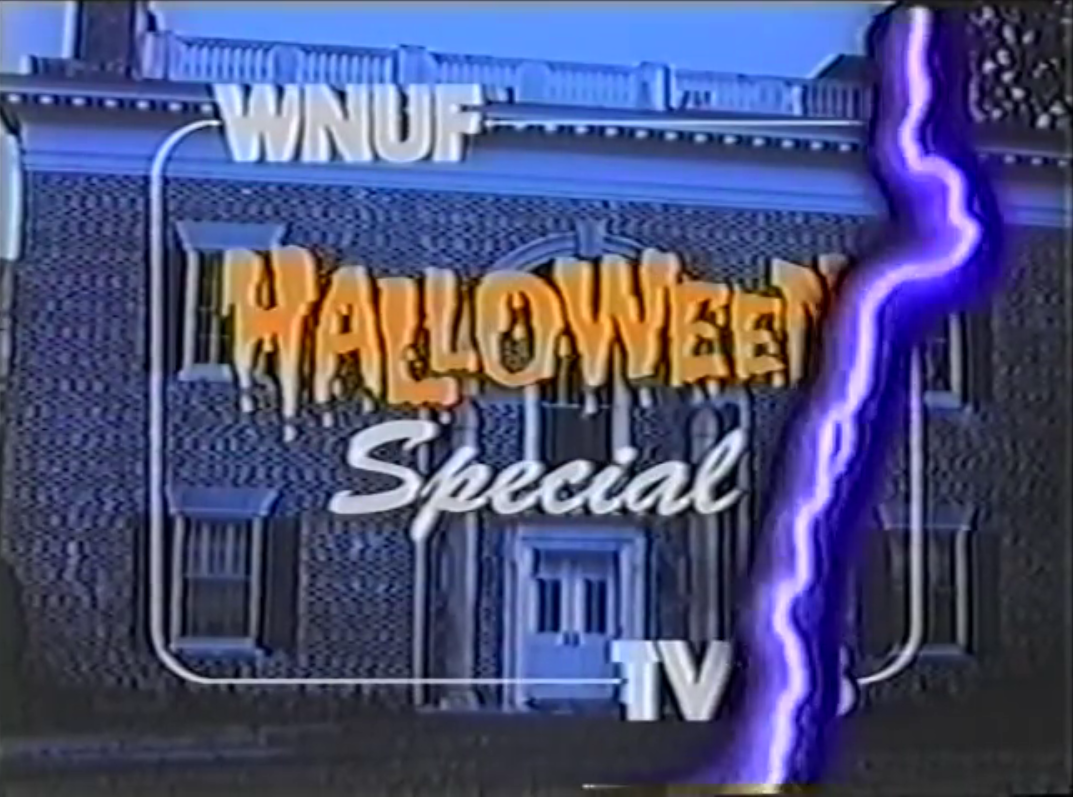

On October 31, 1987, residents of River Hill, Maryland, witnessed one of the most horrifying public access broadcasts in history; on that night, a news crew and a pair of occultists participating in live special investigating — yep, you guessed it! — a haunted house were murdered over-the-air. The special aired only once, and no copies of it were ever made public… until 2013!

That sounds too good to be true, right? Well, it is. The WNUF Halloween Special is a faux-documentary that imitates a late 1980s public access broadcast in much the same way War of the Worlds imitated a news bulletin and Ghostwatch imitated a live talk show. The movie, a wicked 83 minutes of VHS-glitched nostalgia, follows the WNUF crew, which includes a pair of bickering anchors and a surly mustache which also doubles as a field correspondent, through their yearly Halloween special. This time is a little different, however, as the mustache, a man named Frank Stewart, is going into the infamous murderhouse with a pair of famous paranormal researchers and a priest to discover what grisly secrets are hidden inside its walls.

To say that The WNUF Halloween Special inspired the same kind of reaction as War of the Worlds or Ghostwatch wouldn’t just be overstating its popularity, it would be pretending it’s even in the same ballpark. WNUF stands apart from the other two as it’s clear the film isn’t a hoax of the same scale, and, probably because of that, immediately reveals itself as an elaborate fraud. The backstory is too well constructed, the acting too spot on, and the plot too linear for it to ever be more than an extremely clever hoax. And that isn’t touching on the fact that by 2013 the Internet was enough of a factor in the daily lives of people that an even an extremely clever hoax like WNUF could be dispelled in a matter of hours. But that didn’t stop the creators of the film from trying. As co-director Chris LaMartina explained in an interview with the New York Times:

To get the word out about my film my producers and I drove around and left copies of the tape at different places. We did that for about two months. We left about 50 tapes at a VHS convention in Pennsylvania. We left copies in the bathroom, or on tables and just walked away. I would drive down the street in Baltimore and throw them out my window. It was a whisper campaign. I hoped somebody would write about it online. The distribution of the film became a narrative for me as a filmmaker. My goal was if I fooled one person, I did my job.

In many ways, WNUF and Ghostwatch are cut from the same cloth. They both unfold as real in their alternate realities, never breaking continuity for their durations, and they both go to great pains to establish authenticity. Ghostwatch flashed the BBC’s actual call-in number for its live audience, and WNUF includes dozens of period-appropriate fake commercials to simulate the feeling of watching a live television broadcast. But they both have very different perspectives on how they should be using the mechanics of their alternate realities to inform viewers in our real reality. Ghostwatch treats its parapsychologist, Dr. Lin Pascoe, as a real person and gives credence to her opinions on the supernatural as it progress; at various points throughout the film, she’s attacked by a colleague from New York who views parapsychology as a pseudoscience, but, in the end, she’s proven right. WNUF takes the opposite approach. While it establishes it’s paranormal researchers, Louis and Claire Berger, as sympathetic figures, it’s ending comes as a shock not because they’re proven right, but because they’re proven to be very, VERY wrong about the nature of the evil that haunts River Hill.

Early in The WNUF Halloween Special we’re introduced to a group of far-right religious zealots who believe Halloween is the Devil’s work and that celebrating the holiday is an abomination against God. Much like the fake commercials that interrupt the film and help to establish its authenticity, the zealots also interrupt the live broadcast and foreshadow much darker things to come. By film’s end, then, it’s no surprise that the true monsters are the religious extremists who hate Halloween and would literally cut a man’s tongue out to teach him a lesson. Poor Frank, he had such a quick wit about him.

WNUF uses its fake reality to goof on our real reality where Ghostwatch rested on trying to embrace our suspension of disbelief. The shock in WNUF comes from the fact that the real monsters are always in front of us, literally, but we keep looking off into corners of the screen for moving drapes or listening for creaking doors. It’s not a particularly deep statement. It is, however, a clever one in the sense that it plays off the audience’s expectations and then subverts them in the simplest and most obvious way possible. Ghosts aren’t real, right?

Unfortunately, few outside a very devoted community of horror enthusiasts are familiar with The WNUF Halloween Special. It hasn’t had the same impact as War of the Worlds or Ghostwatch, even if it most definitely is a spiritual successor to both projects. Is that because as an audience, today, we’ve become desensitized to mass media hoaxes? If our current election cycle is any indication, that’s not the case. So, then, what’s next? Who creeps in out of the dark to scare us all with another elaborately-constructed Halloween prank?